Millions of tourists visit Hawaii every year. The Hawaii Tourism Authority remains silent on the fact that 75% of slugs on the Island of Hawaii test positive for Rat Lung Worm. Cases on Maui have been confirmed.

The good news is that rat lungworms prefer to enter the body of a rat and are not looking for humans. The even better news is only five visitors to Hawaii Island this year had been infected with this potentially debilitating parasite. Last year 10 tourists got sick after leaving the State of Hawaii.

However, eating a worm by accident can happen and the entire state of Hawaii is at risk. A little bit of prevention goes a long way towards protecting your health from this destructive parasite.

What happens if you accidentally swallow a worm that invaded a fruit or vegetable? The Hawaii Department of Health Disease Outbreak Division suggests persons with symptoms should consult their healthcare provider for more information.

Hawaii’s Department of Health said yesterday it received confirmation from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control of the three recent cases and that they were unrelated.

How to get sick after eating a Rat Lung Worm

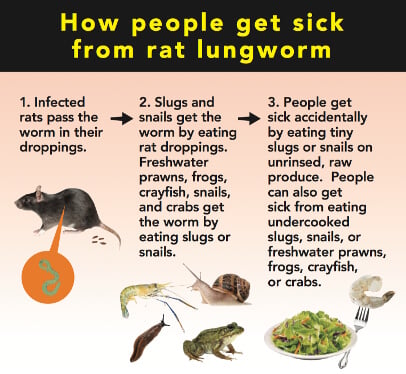

Angiostrongyliasis, also known as rat lungworm, is a disease that affects the brain and spinal cord. It is caused by a parasitic nematode (roundworm parasite) called Angiostrongylus cantonensis. The adult form of A. cantonensis is only found in rodents. However, infected rodents can pass larvae of the worm in their feces. Snails, slugs, and certain other animals (including freshwater shrimp, land crabs, and frogs) can become infected by ingesting this larvae; these are considered intermediate hosts. Humans can become infected with A. cantonensis if they eat (intentionally or otherwise) a raw or undercooked infected intermediate host, thereby ingesting the parasite.

This infection can cause a rare type of meningitis (eosinophilic meningitis). Some infected people don’t have any symptoms or only have mild symptoms; in some other infected people the symptoms can be much more severe. When symptoms are present, they can include severe headache and stiffness of the neck, tingling or painful feelings in the skin or extremities, low-grade fever, nausea, and vomiting. Sometimes, a temporary paralysis of the face may also be present, as well as light sensitivity. The symptoms usually start 1 to 3 weeks after exposure to the parasite, but have been known to range anywhere from 1 day to as long as 6 weeks after exposure. Although it varies from case to case, the symptoms usually last between 2–8 weeks; symptoms have been reported to last for longer periods of time.

You can get angiostrongyliasis by eating food contaminated by the larval stage of A. cantonensis worms. In Hawaii, these larval worms can be found in raw or undercooked snails or slugs. Sometimes people can become infected by eating raw produce that contains a small infected snail or slug, or part of one. It is not known for certain whether the slime left by infected snails and slugs are able to cause infection. Angiostrongyliasis is not spread person-to-person.

Diagnosing angiostrongyliasis can be difficult, as there are no readily available blood tests. In Hawaii, cases can be diagnosed with a polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test, performed by the State Laboratories Division, that detects A. cantonensis DNA in patients’ cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) or other tissue. However, more frequently diagnosis is based on a patient’s exposure history (such as if they have history of travel to areas where the parasite is known to be found or history of ingestion of raw or undercooked snails, slugs, or other animals known to carry the parasite) and their clinical signs and symptoms consistent with angiostrongyliasis as well as laboratory finding of eosinophils (a special type of white blood cell) in their CSF. There is no reliable diagnostic test available to detect previous infections of angiostrongyliasis.

There is no specific treatment for the disease. However, the Governor’s Joint Task Force on Rat Lungworm Disease recently published preliminary evidence-based clinical guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of neuroangiostrongyliasis. The parasites cannot grow or reproduce in humans and will die eventually, causing inflammation. The preliminary guidelines call for a complete neurologic examination; a detailed history of possible exposure to snails/slugs, rats, or other things suggesting a risk for infection; and a lumbar puncture, or spinal tap, to diagnose the disease and relieve headaches caused by the disease. Steroids should be given as early as possible to reduce inflammation. Anti-parasitic drugs, such as albendazole, may be helpful, although there is limited evidence of this in humans. If albendazole is used, it must be combined with steroids to treat any possible increase in inflammation caused by dying worms.